|

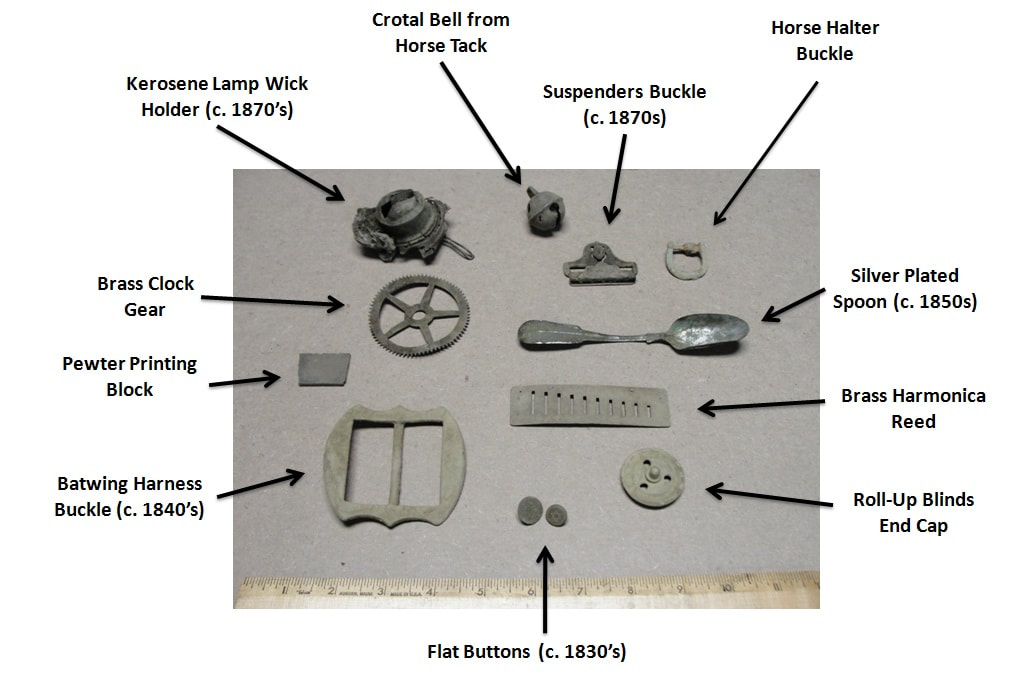

By chance I found this homestead driving by it one spring day. The foundation is right next to the road and very distinct, but usually masked by brush during the year. There are actually a surprising number of sites like this on back country roads. Homes built in the early or mid 1800’s and then abandoned during the first few decades of the 1900’s are plentiful and in many cases there wasn’t any reason to formally demolish them. They just burned down or fell in on themselves over the years. Like many others, it was used as bottle dump in the 40’s, but it doesn’t have a full cellar as it was built on a rock ledge so the “trash” is limited. I’ve known about the spot for several years since I first passed by it, but the chance to finally detect around it came from a random local connection and I leapt at the opportunity. In my experience, sites like this have rarely been detected by others and can offer a particularly complete look at the inhabitants. The structure itself is built into a prominent ledge of slate and I quickly found out that behind the house, usually a very productive place to search, was nearly a sheer cliff. On either side of the house were incredibly steep slopes where I had trouble even keeping my footing. Digging was more of a challenge, but if I was prone to losing my balance on hillside then so would the occupants. Spots like that are usually very dense with lost relics and this was no exception. Almost immediately I dug a few large pieces of iron and then a high signal revealed an intact batwing buckle! Those were produced around the 1830’s and finding one is a sure sign that the spot hasn’t been searched before. I continued to carefully grid the slope turning up a wide variety of ferrous and non-ferrous relics. Most relics seem to date from the 1870’s to 1890’s which is common even if a site spans the entire 1800’s. In the early 1800’s brass and copper was usually worked partially or entirely by hand making it relatively expensive. Industrial manufacturing brought down the cost of goods with brass and copper. As they become more plentiful they also became more disposable which translates to a greater proportion of lost or discarded relics from that time. Behind the slate cliff there were also the clear signs of a roadbed. Initially I thought this was a modern addition, but review of the county maps showed a single reference to a sawmill and an accompanying mill pond. Of the four maps though, only one had the mill marked which is unusual. At the end of the road there was a flat area overlooking the river as well as a few piles of fieldstones but nothing distinctive. It wasn’t until I got right up next to the river that I found two parallel walls of rock and the washed out remains of the slipway. The site of the mill! There were very few signals in the ground around the mill site and I only found 3 relics that may be related. The short period that the mill existed (based on the maps) is uncommon, but would explain the scarcity of targets. My hypothesis is that the mill was washed away in a flood fairly early on in its existence and wasn’t rebuilt. In 1888 there was a well documented flood in the region that destroyed much of the water-powered industry in Nassau and Malden Bridge. It’s very possible that this mill was also a casualty. After the initial gridding of the home site and the mill I had recovered over 100 relics in various conditions and the work now shifted to cleaning, preservation, and research of the artifacts. The methods I use depend on the age, material, and condition of the relics as well as the potential for information. Anything that has writing or could have writing is cleaned with the utmost care to save as much of the lettering as possible for research. For other relics, like iron, the focus is on preservation and stopping the oxidation which would eventually consuming the object. As a case study I’m going to show you the process for the large cent I found at the site. In the first photo you can see where we start off right out of the ground. These coins were made of nearly pure copper with no intentional alloying metals. As a result they’re particularly vulnerable to soil chemistry and moisture. The dirt is heavily and fully encrusted to the copper and the natural patina that formed from the 160+ years of burial is bonded to that dirt. In some cases I make the decision to keep that patina layer, but with later large cents the relief of the design means that good definition is usually found even without the patina layer. For older coppers, like colonials, the opposite is nearly always true and the removal of the patina takes any detail with it. The technique I used was simply mechanical removal of the dirt/patina layer with a wooden point. After the coin dries the layer begins to flake off naturally and the wood point can be used to tease off the more stubborn parts without scratching the underlying copper. For a coin like this it can take 10-15 minutes and the result is what you see in the second photo. While the dirt/patina is removed, there’s still very little visible detail and it’s not particularly attractive. This is where contrast comes in and why it’s so important. The higher points and details are only visible if there’s a difference in color or texture that the eye can discern. By polishing the coin slightly, the superfluous dust is taken off of the high points, but left in the creases and around the edges helping them “pop” and making the coin look more like it would have originally: The final product isn’t something that would pass muster with a coin collector, but for historical information the type, date, and even die varieties are easily determined. Various relics turn up a site like this and while many are everyday objects, each one gives a little clue as to the time span of the homestead and who lived at the site. Below are just some of the many relics that I uncovered over the few hours I was there. The most amazing relics to turn up, were actually a series of brass pieces that at the time of excavation I thought were just some random hinge fragments. They were grouped together nearly in the same hole, but it wasn't until I started cleaning them that I realized they all fit together. As it turns out I had stumbled on an incredible piece of American history! The three pieces on the left were obviously shaped to fit together, but the hinge didn't make sense until I examined the last piece of the puzzle. You see, the part on the right is the characteristic shape of a rifle or musket butt plate, a relic that I've found a few times before. However, I noticed a small notch cut into the side which fit the depth and curve of the center brass piece perfectly. Some quick internet image searching turned up precisely what I was looking for. The three brass pieces form what's known as the "patch box" on a Kentucky Long Rifle. The patch box was intended to store the greased patches of cloth that were wrapped around the musket ball, but may have also served as a convenient receptacle for other tools and accessories. These rifles hold a particularly important place in colonial American history. For starters they were more accurate than any muzzle loading muskets that came before, and perhaps more importantly they were the first truly American firearm. Muskets like the Brown Bess were imported from Europe, but the Kentucky Long Rifle was initially made by German craftsmen that had settled in Pennsylvania in the 1730's. Also unlike the Brown Bess, the barrels were rifled inside which imparted a stabilizing spin on the musket balls. This tremendously increased their accuracy, allowing a skilled marksman to hit a man-sized target twice as far as the Brown Bess could (200 meters versus the 100 meters for the Brown Bess.) The trade-off was that the barrel was slower to load and if improperly cared for, could foul and jam upon firing. Still, this was the preferred rifle among pioneers and saw use during the French and Indian War, Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and perhaps right up until the American Civil War. The rifles and the skilled marksmen that wielded them developed a fearsome reputation among the British during the Revolutionary War and their use was pivotal during the Battle of Saratoga. However, these rifles were not produced in anywhere near the quantity of other muskets of the time and were considered prize possessions by their owners. Each one was laboriously crafted by hand and it's estimated that fewer than 73,000 were manufactured over the near century of production. These recovered pieces actually demonstrate their hand-crafting in the form of assembler's marks. Sort of like a serial number, each individual brass piece of this gun was stamped with a number, in this case "88," by the gunsmith to identify which assembly they were intended to fit. Since no two guns were identical, the cast pieces had to be carefully shaped to fit together and if lost it would be difficult or impossible to replace the part.

Unfortunately none of the pieces I recovered have the maker's signature so it's difficult to pinpoint precisely when and where this Kentucky Long Rifle was manufactured, but this is a tremendously rare find and by far the highlight of the day! That's everything for now, but you can be sure that there's more to find at this spot and that I'll be back many times!

2 Comments

|

Author

Max Cane is an avid detectorist and historian specializing in 18th century sites, but exploring all sorts of historical structures. At both ruins and existing homesteads he recovers, preserves, and researches the artifacts that settlers lost long ago. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

|

Lost homesteads and structures are all around us and virtually every section of woodland I investigate has at least one hidden amongst the trees. I'm continually amazed by just how many there are waiting to be found and the history that they represent. If you would like to read more, I have many previous articles in my archive! Click the below link to browse through them: Article Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly