|

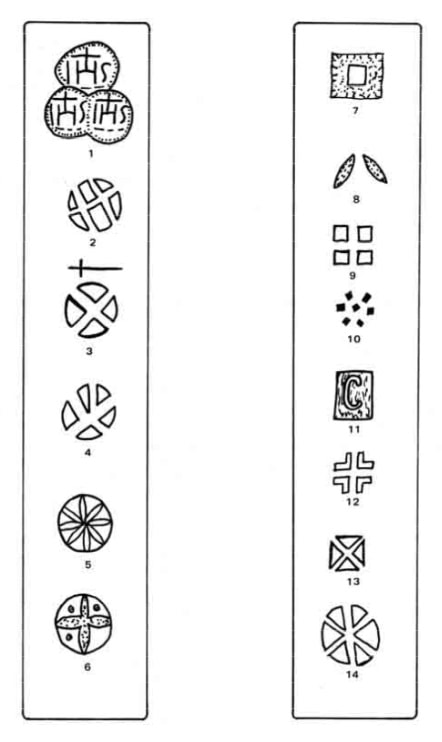

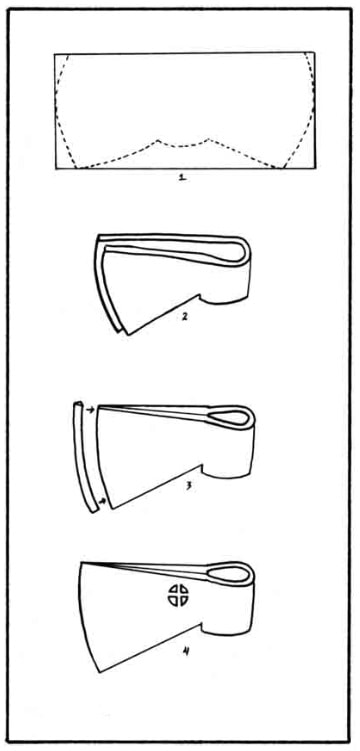

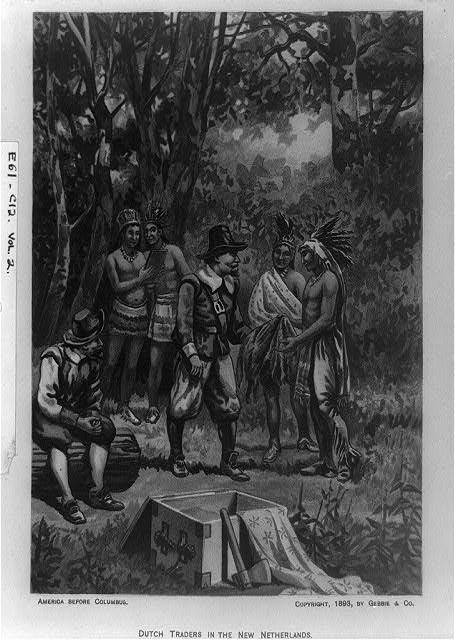

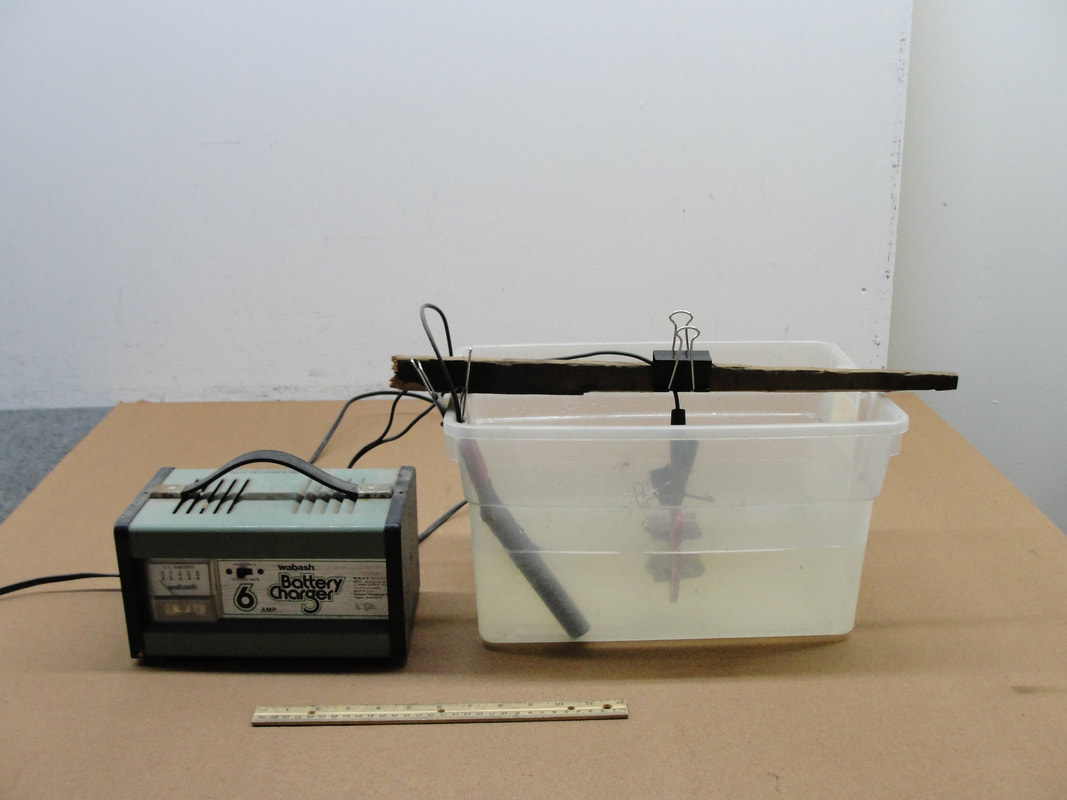

I'm often asked if I come across Native American artifacts during my historical detecting surveys and unfortunately it's extremely rare. I have no doubt that I've unwittingly crossed dozens of sites over the years and perhaps some of significant historical importance, but the sad fact is that I would never know with just a metal detector. The vast majority of indigenous artifacts are made of materials that have no conductivity and therefore would not register on the detector, but there are two notable exceptions to this. The first are copper culture artifacts manufactured by tribes thousands of years ago using nuggets of copper dug and worked in their metallic form. Copper culture artifacts center around the Great Lakes and have been known to turn up in central New York, albeit rarely. The other type, and the subject of this post, are metal objects manufactured and brought to the New World by Europeans specifically for trade with Native American tribes. This practice began almost from the very beginning of a European presence in the Americas. Indeed, the Desoto expedition of 1540 noted that they found European iron axes, beads, and rosaries already in native villages. While I've long been aware of these relics existence, it's important to note that actually finding one is extraordinarily rare. For starters the bulk of this trade occurred during the 16th and 17th centuries, well before extensive European settlement in the New World had occurred. And as European settlement did expand, Native Americans were pushed progressively further and further westward so trade often took place along then-wilderness boundaries like Ontario and Michigan. It's also important to keep in mind that by design these pieces were considered precious by their owners; losing one would not have been a common occurrence. So you can imagine that when I turned up just such and artifact this past year I was shocked, and more than a little skeptical that I had indeed found a trade artifact. The above artifact is the piece in question. I was surveying about two acres of flat ground rising above a bend in the Kinderhook River when it popped up. It's a particularly odd spot that towers 20 feet over the river on three sides and has an even higher ridge isolating it along the fourth. The ground is almost perfectly flat, but very sandy so all but useless for farming. I was only spending extensive time detecting there because I had stumbled on the site of a late 19th century campsite and was gleefully pulling coins out of the ground left and right. There were a small number of 19th century iron relics too, including a horseshoe and shovel handle, but not enough that any structure was indicated. The axe head appeared well away from the coin scatter on one of my wide sweeps. At first glance it seemed like any other small hatchet so I gave it little attention at the time. It wasn't until I cleaned off the dirt back at home that I noticed the faint touchmarks under the rust. The significance of the touchmarks is that they were added by the blacksmiths as one of the final steps in the manufacturing process, but most importantly they're diagnostic of Biscayne trade axes. There's some debate as to the exact nature of the marks, but in general larger axes will have multiple marks that seem to correspond to the weight (2 marks for a 2lb axe, 3 for a 3lb axe, etc.) There are numerous exceptions though. It's also not known if the marks were unique to a specific blacksmith, region of manufacture, or even date range. What is known is that there's quite a variety. Below are just some of the documented touchmarks. Finding an axe head with one that matches a known mark was a solid indication that I had uncovered a trade axe (the touchmark on this piece matches number 3) and not just a 19th century hatchet. Another clue is the shape of the axe head itself, flat top with a curved blade and an egg-shaped eye. This is important because Biscayne trade axes were hand-made, but mass produced using the same method resulting in a consistent form. A butterfly of iron was hand-wrought and then folded over onto itself and hammered until the seam was gone. To keep the blade from splitting over time, a separate tip was beaten into the metal until it completely fused with the original piece. Finally the appropriate touchmarks were hammered into the still-hot metal. Biscayne trade axes get their name from the provinces and districts in South-Western France and Northern Spain where the iron was mined and the axes were manufactured. They were first brought over by the Spanish in the early 16th century, but the French soon followed and by the end of the 17th century even the British were manufacturing copies for export to the Americas. For the most part it was all with the same purpose in mind; obtaining furs. Exporting furs and pelts from the New World for sale in Europe was a tremendously lucrative activity for both the Europeans and the Native Americans. Muskets, silver jewelry, and cloth were all highly desirable for the Native Americans, but it seems that the simple iron axes were particularly sought after. On archeological digs, trade axes have been found buried with their owners suggesting that they were valuable and personal pieces. There's a European tendency to cast the tomahawks as fearsome weapons used by the indigenous persons (the term tomahawk being a catch-all, but encompassing trade axes) for battle between tribes and against the Europeans themselves. However in all likelihood their value and utility was probably more tied to their use in day-to-day life. Stone axes were fashioned with great care for thousands of years, but even the best probably fell far short of the versatility of an iron axe. The iron was much less fragile than a stone blade and resharpening of the iron could be done quickly with little experience using a simple whetstone. These trade axes were compact and easily carried long distances with uses too many to count. Now that I was certain I had found a trade axe, the difficult part was restoring and preserving such a precious artifact. The sandy soil had allowed the water to drain quickly over the centuries so it was actually far less rusted than the average iron artifact. However the water trapped within rust facilitates further oxidation which will flake off and expose more metal eventually destroying the artifact. To prevent this destruction the rust must be removed and there are a few methods to do that with varying levels of impact to the underlying metal. I wanted to be sure to preserve as much of the artifact as possible while still retaining fine details like the touchmarks. This meant that electrolysis was my best bet. Electrolysis is accomplished by constructing a simple electrochemical cell. The artifact is submerged in water and hooked up to a power source so that the artifact itself becomes a negatively charged cathode. The positively charged anode is made from a carbon rod also submerged in the water. Sodium Bicarbonate is added to the water to facilitate charge transfer and when the power supply is engaged the negatively charged ions on the relic (oxides, chlorides, carbonates) that make up the rust migrate to the positively charged carbon anode. Conversely carbon migrates to the iron, but since it's insoluble in the water and doesn't adhere easily to the iron, the layer is minor and it can be removed later. This process leaves the positively charged iron alone and as long as the voltage is kept low and the current moderate (~2 amps in my setup) the process proceeds steadily and with little risk to the artifact. Every two hours the relic was removed and a simple brushing with water would flake off loosened rust. Bare, clean metal was visible even after the first treatment stage and as the process continued more and more of the original piece was brought back to life. The above images show the progression of the trade axe from start to finish. The middle photo is from the halfway point: roughly 4 hours of treatment. All told the process took about 8 hours plus scrubbing with a brass-bristled brush to remove the carbon deposits without scratching the original iron. Once I was sure that absolutely all of the rust had been removed, the axe was put into molten wax at about 150 degrees Celsius. This forces any remaining water on the axe to boil off completely dehydrating the microscopic pores. The voids in the surface that were once occupied by water are then back-filled with wax. Once no more bubbles could be seen emanating from the axe, it was removed and allowed to cool. Most wax drips off the hot metal, but just enough adheres to create a thin layer which will protect it from any atmospheric moisture going forward. Once the process was finished the touchmarks became clearly visible on both sides. The pores visible all over the artifact are not from the electrolysis, but instead iron that was converted to rust in the ground. This metal was lost long ago, but interestingly it reveals the underlying grain ridges of the wrought iron that was created by the blacksmith's folding and hammering all those centuries ago. Overall it's an exquisitely preserved specimen. The blade is intact and has the original curve as well as a surprisingly sharp edge. It clearly wasn't discarded due to damage and so it must have been accidentally lost. Perhaps the most interesting questions surrounding this artifact are how and when it came to be lost along the side of the Kinderhook creek in Eastern New York. While trade axes have been found on East Coast archeological sites, it's extremely rare. This particular touchmark is attributed to French manufacture and is found most often in association with Oneida tribe sites. The earliest example was found at a site dating around the 1570s and the latest in the 1670s. While a century range may seem broad, it still says that this piece is at minimum 350 years old and without a doubt predates European settlement of this town by a hundred years. The Oneida tribes inhabited large portions of central New York, but their contact with the French at the time would have been along the St Lawrence seaway and they did not live on this side of the Hudson River. Instead it seems likely that this trade axe made it's way down from Lake Champlain to the Hudson River valley through inter-tribal trade. The Kinderhook is a tributary of the Hudson river and in the fields along the Kinderhook I've personally found a number of 2000-3000 year old stone points suggesting common indigenous occupation. Native American travel along the Kinderhook River may have been common, but it's still an incredible journey to imagine. At the time the 250 mile journey from Montreal to the Kinderhook may have been conducted to some extent by canoe, but maybe entirely on foot. At a minimum it took several weeks, but perhaps it was over the course of many years or even an heirloom passed down through generations. I don't discount the possibility that this was the site of an indigenous settlement and I just happened to stumble on the only metallic relic present. There could be hundreds of stone points and pottery fragments under the forest loam, but so far I haven't encountered any. It's also possible it was a convenient campsite on a canoe journey along the river or during a hunting party. I can't form much of a conclusion from a single artifact, but it's amazing to reflect on what it only hints at. What I do know is that it speaks to a much longer occupation of this land. It's easy for me to get bogged down in the 200 year history span that the local dutch settlers started, but in truth every day I walk over thousands of years of history largely ignorant. This 350+ year old piece is just the tail-end of perhaps 10,000 or more years of indigenous history along this river. Entire civilizations rose and fell as generations of people traveled along this same river isolated by an ocean. Compared to that untold story and the journey of this simple iron axe, the late 19th century coins and campsite relics seem downright quaint. .

3 Comments

|

Author

Max Cane is an avid detectorist and historian specializing in 18th century sites, but exploring all sorts of historical structures. At both ruins and existing homesteads he recovers, preserves, and researches the artifacts that settlers lost long ago. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

|

Lost homesteads and structures are all around us and virtually every section of woodland I investigate has at least one hidden amongst the trees. I'm continually amazed by just how many there are waiting to be found and the history that they represent. If you would like to read more, I have many previous articles in my archive! Click the below link to browse through them: Article Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly