|

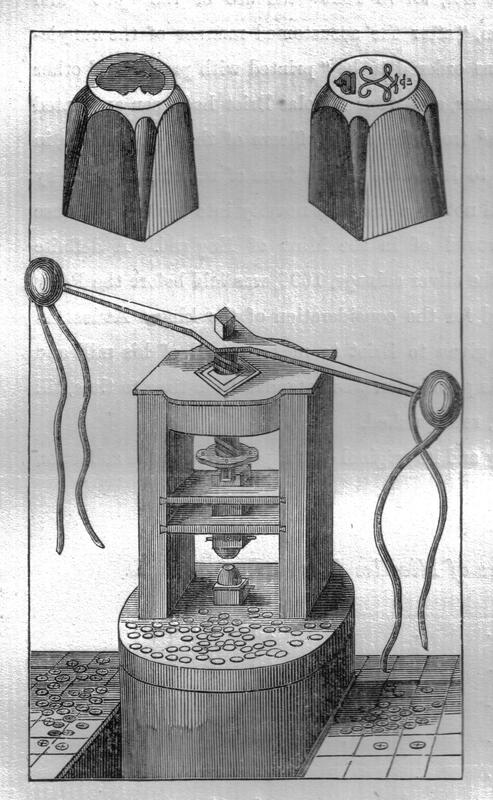

These fascinating and unique coins hold a particular nostalgia for me because a Vermont landscape copper was the second colonial copper I ever unearthed. In hindsight this was particularly startling given their general rarity, and at the time I was completely unaware of both the existence of these coppers and the history behind them. The research that followed is some of my favorite and each additional Vermont copper I’ve uncovered since then has only added to the incredible story of the most unique mint in early American history. First and foremost, these coppers were not issued by a state, but rather the independent Republic of Vermont. In 1777 Vermont declared their independence from British rule, but they weren’t recognized by the Continental Congress due to competing land claims with New York. While many citizens of Vermont fought with the Continental Army and strongly supported the cause of independence, at the legislative level there was friction between Vermont and the 13 Colonies and for a time Vermont was in negotiations with Britain to rejoin the Province of Quebec. The major surrender of British troops in 1781 and the general tide of the war turning ended those negotiations, but there was a level of mistrust for years afterwards. The matter of bringing Vermont into the United States was raised several times by the Continental Congress between 1777 and 1785, but without any action. It wasn’t until 1787 when Alexander Hamilton proposed that New York accept Vermont’s admission to the Union that there was progress. The idea was that the admission of a northern state would act as a balance to Kentucky, a southern state, also being admitted. A deal was struck where Vermont would compensate New York for the disputed land and the amount of $30,000 dollars was to be distributed among the landowners on former New York land patents. Vermont was finally admitted to the United States in 1791 as the 14th state, with Kentucky added shortly afterwards as the 15th. During the time between the end of the war and the formation of the US mint (1792), commerce was hindered by an acute shortage of coinage with which to make change. During this period several states stepped in with their own coins (Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey), but the design of Vermont’s coins were quite unique and reflected a great deal of their identity both as a Republic and a potential state. The obverse depicts the sun rising over the green mountains with a plow in the foreground. The designer’s intention in depicting the plow is not explicitly known, but it’s theorized to be a reference to the biblical phrase “swords to plowshares.” The lettering "Vermonts. Res. Publica" is a Latin abbreviation for The Republic of Vermont. The reverse design is actually stolen from an earlier token, the Nova Constellatio, which itself was copied from a pattern coin designed by the Founding Father Robert Morris. The eye of providence is surrounded by the Latin phrase “Stella Quarta Decima” meaning the 14th star. It's believed that this was very pointedly included to show the desire of Vermont to become the 14th state even while they were minting their own currency. This idea is supported by the fact that the Vermont legislature would refer to itself as a state in legislation and even the 1785 act authorizing the coining of copper coins has the phrasing: "...the exclusive right of coining Copper within this State for the term of two years..." These coppers were officially sanctioned by the Vermont House of Representatives, but the coining itself was done as a private enterprise. Reuben Harmon, Jr. petitioned the legislature for the right to coin the coppers which was granted with the stipulation that the design and motto be approved by a committee and also that the coin weight be a consistent 160 grains of pure copper. Harmon's mint was a tiny 16’ by 18’ shack along a stream in Rupert Vermont. He had a supply of copper as well as coining equipment, but lacked the skill to make the dies himself. Instead he partnered with the silversmith firm of Daniel Van Voorhis and William Coley of 27 Hanover Square in New York City and it’s believed that William Coley did the actual die-making for the first coins produced. Die making in those days was a painstakingly slow process. A mirror image of the final design for each side of the coin would have to be cut into two pieces of iron. Die makers would possess sets of punches for letters and certain features, but would then have to sharpen or add additional details to the design by hand. Fixing an error was usually impossible and given the time it took to make a single die, minor errors would often just be left in the final design. Even with the best of skill, the nature of making each die by hand meant that no two were exactly alike. Once the metal die was completed it could then be hardened and used for coining, but the dies would wear out or break frequently and if a second die wasn’t already finished the coining would have to stop until the die maker could prepare the next one. This explains why there are a number of different Vermont landscape coppers varieties and may even explain why certain die combinations are extremely rare today. If a die broke after only a small number of coins, it would have been replaced with a completely different die ending the run of that variety. It's believed that in that first year, 1785, few coins were actually produced. A variety of production issues slowed down the minting and it was also decided that the coins were too heavy compared to other copper coins in circulation. This would result in the coins being melted down for their copper, so permission was granted by the legislature to reduce the weight to 115 grains. The design on the reverse was also changed somewhat, although the reason behind this is unknown. Despite their unusual appearance in comparison with British halfpennies and Connecticut coppers (which strongly resembled the British halfpenny) the landscape coppers were well received by the public. There's a contemporary review in The Massachusetts Centinel announcing the arrival of the coins in New England which says: "The coinage is well executed; and the Device is sentimental, ingenious, and beautiful." Despite this it was still decided sometime in 1786 to radically change the design of the coin. In October of 1786 Reuben Harmon, Jr. went back to the Legislature to get a 10 year extension on the right to coin the Vermont coppers. He was granted an 8 year extension, but the style of the coins was to be changed to more closely resemble the plentiful Connecticut coppers in circulation. The lettering on the coin was also to be changed. Below is one of the changed 1786 coppers: The specific reason for these changes is unknown. Given that the public reception to the landscape coppers was known to be positive, it seems unlikely that the coins had to resemble the British halfpenny in order to circulate. It may have been a change of convenience, as the new design was easier to form dies for. Whatever the reasoning, the early examples of these coins have numerous and serious issues. The example above I excavated from a colonial homestead near a river crossing. The holes in the coin are not the result of ground action, but rather voids in the copper that was used to make the coin. Poor quality copper was a serious issue, but even the lettering along the edges is unevenly spaced indicating poor die work. By 1787 Harmon had partnered with the minting firm of Thomas Machin in New York. Machin produced numerous legitimate tokens under contract as well as running an extensive clandestine operation producing counterfeit British halfpennies. At the time he was angling for the right to coin New York State coppers, but in the meantime they produced Vermont coppers under contract. The most unintentionally humorous of these Vermont coppers produced by Machin can be seen above. The obverse features a good quality bust with "Vermon Auctori" meaning under the authority of Vermont. However the reverse has the seated figure of Britannia and even has the name "Britannia" around the edge and the Union Jack in the shield. This reverse die was taken from one of Machin's counterfeit British halfpennies. The fact that the design is so faint is not a result of the coin being worn down, but instead because the die was used to make so many counterfeit coins that the die itself wore down! It's unknown why a Britannia reverse was used, but it almost certainly wasn't a mistake since thousands upon thousands of this die combination were struck. This is actually the single most common Vermont copper surviving to present day.

Vermont coppers were struck through 1787 and into 1788 when production officially ceased. A New York State act in 1787 made it illegal to pass underweight coppers in trade and if found they could be seized. While the older landscape coppers were heavy enough, many of the newer type were not. That along with the rumblings of federal coinage and the now likely induction of Vermont into the United States meant that the coinage was no longer necessary. It's probable that Thomas Machin continued to surreptitiously mint Vermont coppers for a time, but eventually even those ceased. In the end Vermont had produced far fewer coins than either Connecticut or New Jersey, but their role was no less important in day to day trade. I don't excavate them often, but when I do they're right alongside Connecticut coppers and well-worn British halfpennies suggesting that they circulated far and wide in the same pockets. Today it's estimated no more than 5000 Vermont coppers survive, so each one that I unearth is an actual treasure in more ways than one!

0 Comments

|

Author

Max Cane is an avid detectorist and historian specializing in 18th century sites, but exploring all sorts of historical structures. At both ruins and existing homesteads he recovers, preserves, and researches the artifacts that settlers lost long ago. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

|

Lost homesteads and structures are all around us and virtually every section of woodland I investigate has at least one hidden amongst the trees. I'm continually amazed by just how many there are waiting to be found and the history that they represent. If you would like to read more, I have many previous articles in my archive! Click the below link to browse through them: Article Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly