|

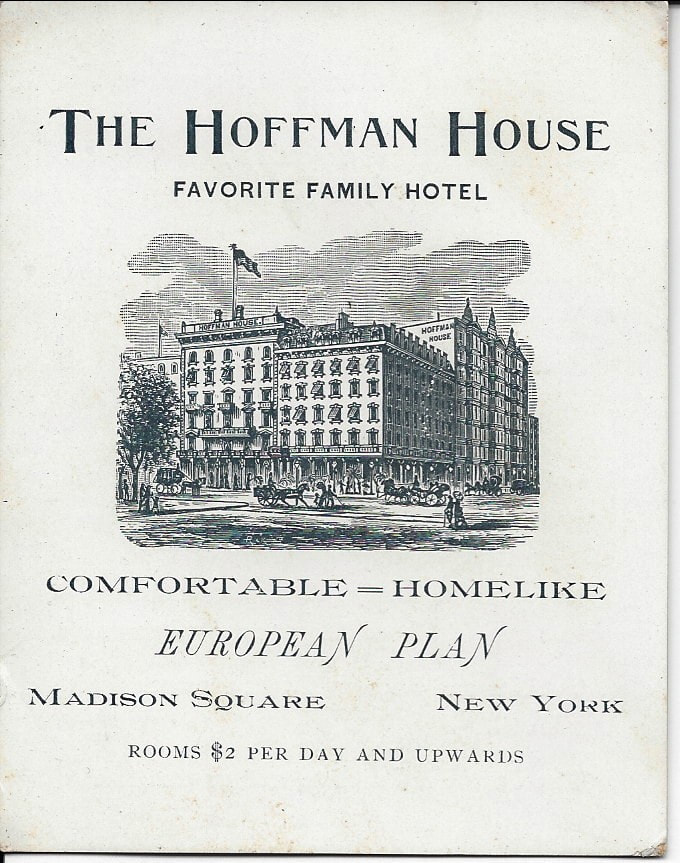

My favorite finds are the ones that lead me down a rabbit hole to a corner of history I never expected to explore! Detecting a farm field this past December, I happened on just such a relic! It was a large sheet of brass that looked just like a cardboard tag complete with the reinforcing collar around the hole. Dusting off the dirt I could see some lettering, but it wasn’t until I fully cleaned it up that I could see it was fairly covered in text. At the top, in the largest letters are: “Hoffman House” along with “25th Street & Broadway.” As usual I did a quick search hoping that I could dig up just a little information online and to my shock there were pages and pages of historical accounts and photographs. Turns out I had found a relic from a famous gilded-age hotel in New York City! Before my deep dive into the history of the hotel, first order of business was to ascertain what the purpose of this brass tag was as that would narrow the date range of the research. The rest of the text read “40 Quarts Jersey Cream”, “Maple Valley Farm”, and “Canaan Four Corners Columbia County New York.” Fortunately I’ve seen similar pieces before and as brass tags like this were used by railroads in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Smaller baggage tags are more commonly encountered and were intended to make it easier for baggage handlers to identify and transfer luggage between trains. While much less common to find, regular freight shipments sometimes had tags made for the same purpose. Based on the text, this tag would have been affixed to the regular shipment of 40 quarts of cream that was carried by rail from the Maple Valley Farm to the Hoffman House in New York City. This tag would also allow the empty crate and bottles to be returned to the farm so that they didn’t have to continuously source new bottles for each shipment. Canaan Four Corners was a stop on the Boston and Albany Railroad which met up with three other rail lines in Chatham, the next stop to the South. As the shipment would have to been transferred at least once to make it to New York City, I’m sure this tag was an absolute necessity to keep the shipment on time! While I can only guess as to how this particular farm in Upstate New York came to be the supplier for jersey cream to the Hoffman House, I have no doubt that it was quite the important account for the Maple Valley Farm! The Hoffman House was founded in 1864 and quickly became known for its lavish artwork, decorations, and cuisine. It was the second hotel built along a stretch of Broadway between 23rd and 25th streets that became home to a number of high-end hotels including the Albermarle and the Grand 5th Avenue Hotel. On the opposite corner was the famous Delmonico’s Restaurant, known at the time as “Del’s.” The Hoffman house quickly became a congregation point for the New York City wealthy and famous and counted among its patrons politicians like Tammany Hall and William “Boss” Tweed. The actress Sarah Bernhardt kept a room there along with newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst. Grover Cleveland even lived at the Hoffman from the day he was elected to his second non-consecutive term as President! An annex was constructed in 1870 which gave the hotel a combined 300 rooms with prices starting at $2 per night; quite the sum at the time! One of the major draws of the hotel was the barroom which featured Wilson Pure Rye Whiskey, the house drink, and numerous expensive artworks. The most famous of which was Adolph William Bouguereau’s “Nymphs and Satyr.” Its subject and presence was scandalous at the time, but lauded by the art world and the notoriety of the painting undoubtedly contributed to the fame and profile of the hotel! William Ballantine wrote in 1884 about the painting: “A magnificent entrance hall contains many very exquisite works of art—amongst others, a large picture of modern date by a native artist, representing a mythological old gentleman, who has apparently given offense to a number of nymphs, who are about to execute ‘Lynch Law’ by consigning him to a pool of neighboring water; really, as far as I am able to judge, it is a very fine work, and is an object of interest both to the citizens and to strangers.” The painting was far from the only controversy related to the hotel at the time. In January 22, 1870, the New York Herald reported that sisters Victoria C. Woodhull and Tennessee (Tennie) C. Claflin had taken Parlors No. 25 and 26 as the office of their new brokerage firm. The women had become famous for successfully establishing themselves in the male dominated world of stockbrokers on Wall Street. The official opening of this office was such an event that the crowds attracted by the spectacle required 100 police officers to keep order! At one point a reporter questioned them, asking: “It is a novel sign to see a woman go on the street as a stock operator, and I presume you find it rather awkward?” Tennie Claflin fired back “Were I to notice what is said by what they call ‘society,’ I would never leave my apartments except in fantastic walking dress or in my ballroom costume; but I despise what squeamy, crying girls or powdered counter-jumping dandies say of me. I think a woman is just as capable of making a living as a man.” Various improvements and updates were made to the hotel through the 1880s and a “Moorish” style addition opened in 1894. In 1895 another, quite different, controversy centered around the hotel’s upgrade to the modern innovation of gas ranges in the kitchens. Such a novelty were gas ranges that even The New York Times felt it was worth reporting, writing: “One of the pleasantest places in the city to dine during the past Summer was in the eleventh-story dining room of the Hoffman House. Probably, however, many of those who went there to enjoy the coolness and the view and the music did not know that all the food served was cooked entirely by gas." However, the writing was not in judgment of the new technology, but rather in its defense. The newspaper adding, “The Hoffman House standard is well known in the hotel world, and its hearty approval of gas for cooking disposes at once of a great many stupid and ignorant objections that one sometimes hears urged.” The hotel continued to be a trendsetting destination into the early 20th century and opened a larger addition in 1907 to great fanfare. Unfortunately this proved to be particularly poor timing as the nationwide financial panic of 1907 severely curtailed their attendance and the hotel ended up bankrupt by 1910. It limped along for a few more years afterwards until finally closing its doors for good in 1915. Today nothing remains of the original buildings. While this little brass tag played a minute part in the saga of the Hoffman house, it’s undeniably connected to all that history! It’s even more incredible that something like that could buried, forgotten in a field for more than a century but once dug up still be connected almost immediately. All those significant events and years of operation, but today I don’t imagine there are many relics like this left from the Hoffman house. I feel so lucky to have rescued a piece of it and been able to connect it to the history it witnessed!

3 Comments

|

Author

Max Cane is an avid detectorist and historian specializing in 18th century sites, but exploring all sorts of historical structures. At both ruins and existing homesteads he recovers, preserves, and researches the artifacts that settlers lost long ago. Archives

January 2024

Categories |

|

Lost homesteads and structures are all around us and virtually every section of woodland I investigate has at least one hidden amongst the trees. I'm continually amazed by just how many there are waiting to be found and the history that they represent. If you would like to read more, I have many previous articles in my archive! Click the below link to browse through them: Article Archives |

Proudly powered by Weebly